Like Father, Like Son

In Robert Walser’s novel, Helbling is an extreme character: he refuses to work, resists the rhythm of society, and only wants to lie still, peacefully, as if the entire world has nothing to do with him. Behind such laziness lies a gentle kind of stubbornness—one that stems from a deliberate refusal, a quiet way of withdrawing from the public narrative.

Xiaohuan also makes his refusal explicit: even the name Xiaohuan itself carries a sense of plain, unperformed joy—something as grounded as soil, as natural as breathing, as present as the quiet happiness one feels while painting. Bu Huan(“Not Joy”) is not negativity nor resistance, but a gesture of refusal, a kind of stability: a simple rejection of the expectation that one “ought to be happy.” It recalls Walser’s notions of “non-action” and “withdrawal,” yet Hei Er Bu Huan (“The son is not joyful”) signals a refusal to cooperate: he does not choose to step away, he situates his life between the everyday and the canvas. He builds houses in Moganshan, paints, reads, grows tomatoes…… His life filled with real colour, concrete days and a person who takes action. For him, a brother-in-law, a son, the woman selling fruit on the street, and the tomatoes he grows all carry the same sincerity. Those are the people and things he paints—bound up with an intimate kind of love, which he, in turn, gives back to us.

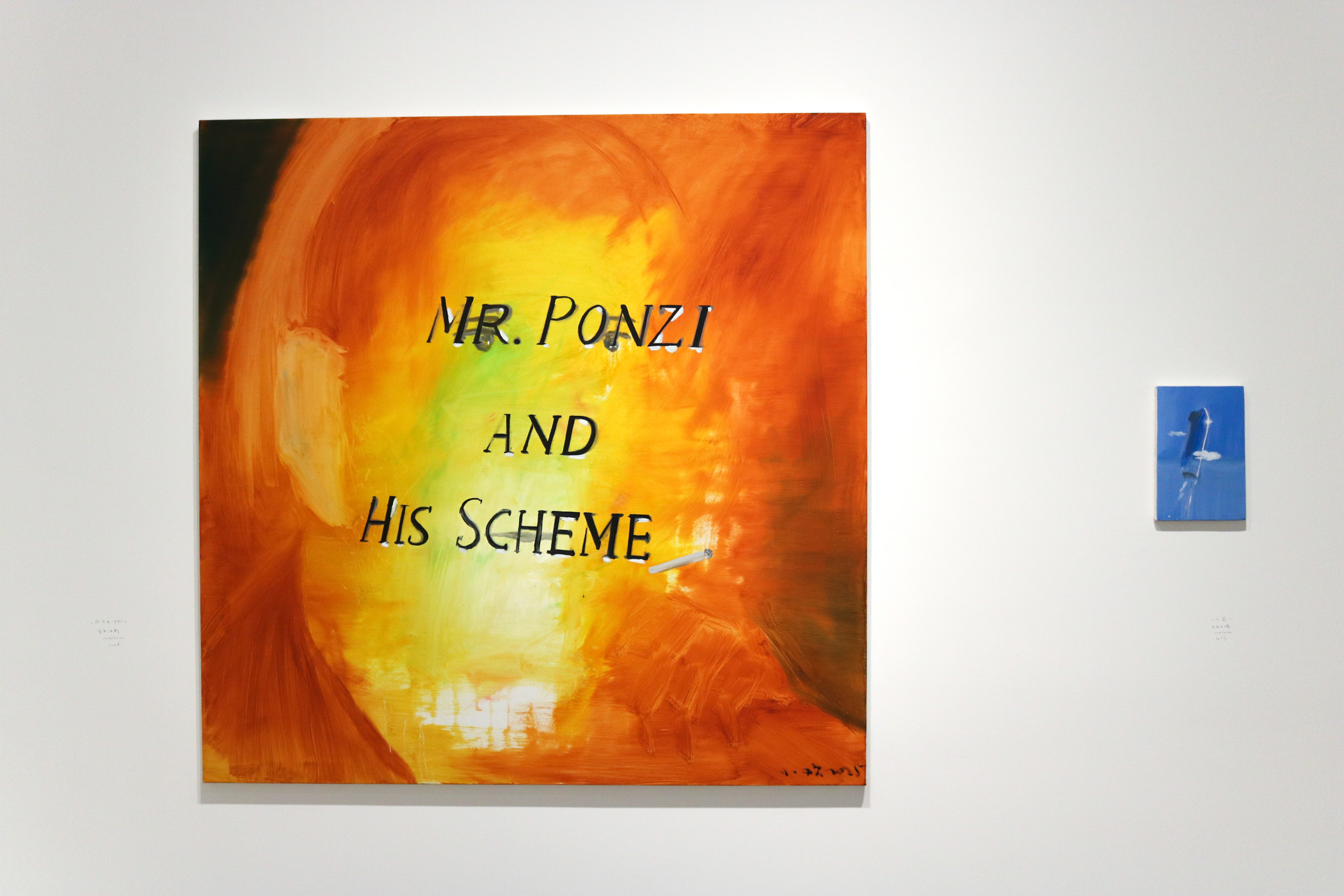

Xiaohuan sees a common posture towards life in his brother-in-law, which is embodied in his work Brother-in-law Had Tried His Best, But Couldn’t Change Anything. The painting depicts his brother-in-law: when he was young, he led people from his village to the city to work, seemingly holding the direction of life in his hands. Yet he eventually went to prison because of gambling, and his family also broke apart. In the end, he lived alone. His life seemed like a failure, yet it was not—as nothing can be truly changed, the only variable is one’s attitude. Xiaohuan’s brother-in-law remains calm and unbothered. Helbling chose to lie down, brother-in-law tried everything with his strength but still could not break through. Xiaohuan finds his own solution between these two sides.

And what way is that? Xiaohuan told us a story:

‘My father once suffered severe burns. It happened one summer night when a pile of straw in the kitchen caught fire. My father had been a soldier, and he insisted on saving our cow. In the end, the cow died anyway—she was even carrying a calf at the time. My father was badly injured and sent to the hospital. We borrowed money everywhere to pay for his treatment, and the debt wasn’t repaid until I was in college.’

‘In that whole ordeal, there was a neighborly love, I experienced it, now I want to return it.’ Xiaohuan does not fall into the nihilistic depression so common today. At the most fundamental level, the reason is simple: he has been loved in this way. Though his days may lack many luxuries, his inner life is full, joyful. As we stood before him, perhaps because we lacked his calm gaze, the mountain air itself felt awkward. We realised that we had come to him with plans, with suspicions, even with strategies.

In August, we visited Xiaohuan’s studio. In the summer, he can hardly paint—it is too hot, and even the insects hide behind his canvases in search of shade. Later we realized that he does not belong to our imagined category of the “artist who withdraws into pastoral seclusion.” First, his environment contains far too many elements we ourselves could not bear; second, he must still engage with us, and with many others like us. Yet he quietly place his attention on the rivers he can walk into, and then keeps painting. That posture recalls a child—not a naive one, but the kind of child who is earnest to the point of stubbornness: if the painting doesn’t work, he tries again; if a colour runs out, he mixes another. He never asks, “Is this worth it?”—because painting, among all possible things he could do, is what gives him the greatest satisfaction. He feels deeply Noah Davis’s condition—being a person of color unable to naturally inherit or appropriate the pictorial lineage shaped by white painters, and so turning wholeheartedly to his own survival—Xiaohuan chose to do the same. He admires the sublimity in Cy Twombly’s work, understands Gerhard Richter’s intelligence in making the image itself a new paradigm of seeing, marvels at Francis Alÿs’s humility and love when observing children, and delights in Julian Schnabel’s raw roughness, that burst of American energy into primal vitality. Xiaohuan is not an elite, so he cannot paint in the bourgeois taste, but he can see the beauty of affluent life in Alex Katz’s works. For him, these are companions and reference points—not the paradigms he ought to learn, simply because he is not them, nor can he ever, or want to become them. He wants to build an ‘image of the human’ grounded in kinship, neighborly love, and everyday experience.

People are always curious about Xiaohuan’s motivations, as if motive were the most important thing. For Xiaohuan, motive is nothing more than a casual‘Because I want to.’ Such an answer both disappoints us and inspires our envy. We are used to cutting life into segments and giving each a title. He has no such intention. His days often pass without any pause: from the sky above to the bed he sleeps in, like a flowing sentence without any punctuation. He keeps paintings, perhaps even forgetting where a particular canvas has left off—but it does not matter. They are things placed casually yet naturally in his life, like his house. If someone were to walk in, they might say it all looks too casual, but that is just the very order of his life.

Beyond the matter of survival itself, we are always used to, or even too eager to attach symbolic meaning to things. ‘Now, Helbling may lie as long as he pleases, no one will care or make a sound of it.’ Xiaohuan continues to paint and live in the mountains. He is neither Helbling nor our idealised projection, but someone who truly live and act.